This series of articles is a partnership between SPECIFIC, SUNRISE and the Active Building Centre.

Our projects work with academic, industry and community partners in the UK and the Global South to research and develop solar technologies and to drive change in the construction industry.

While our projects each have distinct objectives and approaches, our shared message is simple: buildings don’t have to cost the Earth.

Our vision for transformation comes with many challenges across technical, political, social and economic norms. In this series we will share some of the work we’re doing to address each of these.

The first is a Q&A with Carol Maddock and Khushboo Ahire on social work with a community in India, and the idea that change begins at home: with the people who might live and work in the buildings.

In June, Carol Maddock travelled to India as part of the PIPERS for SUNRISE (Public Involvement, Principles of Engagement, Remit and Strategy for SUNRISE) programme to work with a rural community in Maharashtra, India. PIPERS for SUNRISE was established to explore, identify, and embed public involvement and engagement within the wider SUNRISE project, and is now well underway. The next step following the development of a draft strategy for Public Involvement and Engagement was to pilot the methods outlined in the strategy in a real-life context, i.e. in rural India.

To ensure the social impact of our building demonstrators is effective, the strategy needs to be co-produced with local residents. The pilot programme will begin this process of co-creation, with lay people in a pilot community in India helping to refine and/or confirm the operational elements of the strategy that will then be applied in other villages.

Carol Maddock, who alongside Prof Vanessa Burholt is delivering the PIPERS for SUNRISE programme, is employed in the Centre for Ageing and Dementia Research (CADR) Cymru, specifically involved in the areas of Involvement and Engagement in research. Working with Khushboo Ahire and Prof Siva Raju from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), they identified a village called Mograj in Karjat, Maharashtra. Mograj is a medium-sized village about 80km east of Mumbai and home to 630 people, the majority of whom are from Scheduled Tribes. Khushboo spent ten days with local residents piloting various participatory arts-based approaches aimed to encourage public involvement in project activities.

Mograj village, Karjat

GB: First of all, what is public involvement and engagement?

CM: I think they are different things to different people, and that’s why it’s important that we have put [definitions] in the strategy. You’ll read different documents, even journal articles, where people look at things in a slightly different way. But for us, involvement is research that is not done to you, but with you – you’re not participants taking part in a clinical trial or something like that, but actually involved in one aspect, or it could be all the different parts of the research process, from looking at research questions to actually being involved in designing bids and taking part in evaluation. You could be involved in any part of that research cycle. You are an equal partner, and valued for your input as a lay person. So that’s what I would envisage as involvement.

And then you’ve got engagement – letting people know what the project is about, perhaps via blogs or any means to explain [your research] to people so that they can engage in the whole process. They’re being informed and they can start to make enquiries themselves. That’s what I’d see as engagement.

And then participation, an example may be being recruited as a participant in a research trial – what used to be called ‘research subjects’ – or taking part in a focus group. So you’re not having an input into the research aims overall, but you are taking part and contributing.

Each way, whether involvement, engagement, or participation, you are involved in the research process, but with slightly different levels of impact. There are definite contributions in all of them. One of the key things is that you are taking part in the research rather than having it done to you. You are able to shape it more. I do think that it is important that we have defined [these terms] because they are viewed as different things by different people.

“…involvement is research that is not done to you, but with you”

KA: I absolutely agree with Carol, she has rightly mentioned about the true spirit of public involvement and engagement strategies as them being flexible to customise according to the profile of the study areas as well as the participants. Also, while conducting the pilot, it was observed how certain activities like ‘Body Mapping’ lead the participants to introspect and think critically about being aware of their personal health, and how their surrounding contributes towards their wellbeing.

GB: What exercises/activities did you carry out with residents? Did any of them not go as planned?

CM: I don’t speak any Marathi so I wasn’t really taking part in them. Khushboo and I had gone through what we were going to do. I was there as an observer really; it’s quite difficult [to observe] when you’re conducting an activity, you’re not always in a position to see the interactions. You’re making sure people in the group are taking part so it is actually quite nice to have somebody who’s sat back and observing the whole process.

We’d gone via an NGO to make sure we were able to access the participants in the time frame we had. But because it was all done quite last minute, what we explained we wanted over the phone hadn’t quite been understood. We wanted small groups comprised of separate age groups and sexes but when we arrived on the first day there were all these women sitting on the floor, of all different ages, all waiting for us. So we started the first activity not as we would have wished to, because normally you’d explain it, get your consent, and just start with a little group. But we accelerated that process and started off with that mixed aged group of 16 or 17 women. Not ideal at all, but in a way it was useful to be able to explain what we were doing so we could come back knowing that the next time would be easier! The idea was we’d have each of the groups for each of the different techniques, so it’s really quite a time commitment. We wanted each group to take part in these sessions, each proposed at about three hours a session.

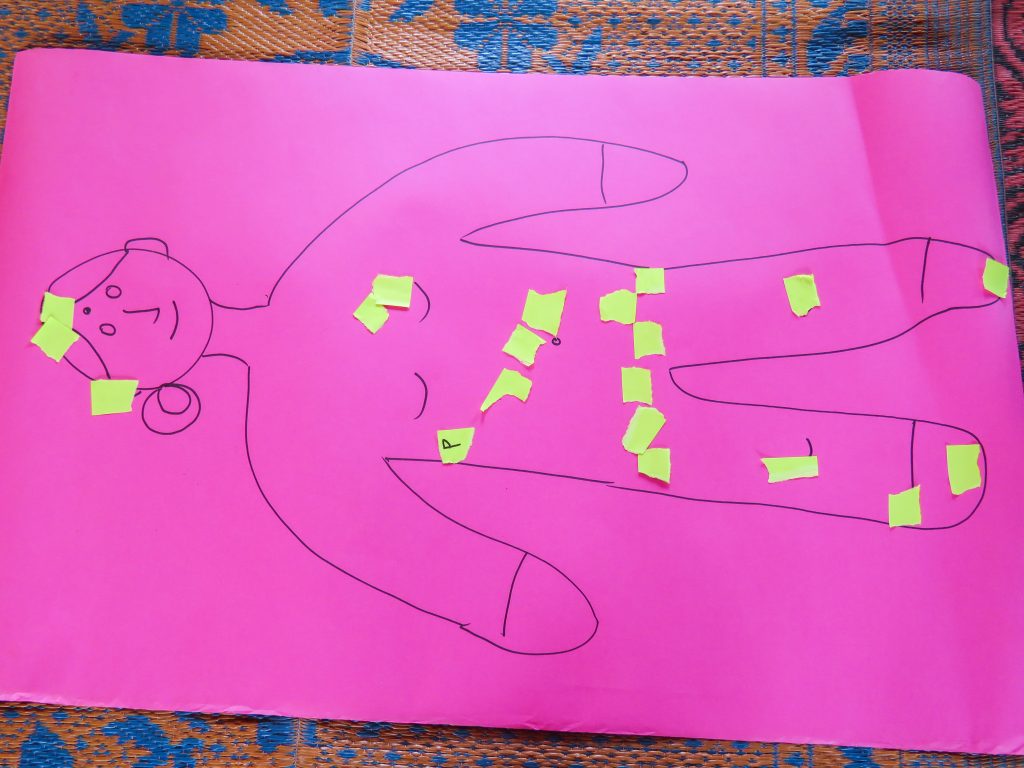

The first [session] was body mapping, where you’re supposed to draw around each other. And I’ve done this in the past and it’s worked OK [in the UK]. You draw around [a person’s body] and annotate it inside and out, detailing, in this case, how you may feel at the end of your day – feelings, emotions, physical attributes and capabilities. But when we were talking about the techniques beforehand with Siva Raju and Khushboo, they were uncertain if this would be something the villagers would be comfortable with, particularly in an introductory session. But the way we’d planned the sessions was to build up pieces of information – about the individual first, then their social relationships in the next technique, and then daily activities and occupations before finally exploring the abilities, choices, and opportunities that will have emerged from the previous sessions. So each one led to another and informed the other. We wanted to be able to do something like that. In the end Khushboo just drew a body shape [instead], so we were able to adapt the technique. It also panned out that there were different literary levels in the group, particularly because we had the mixed group, and some of the younger ones were more confident with drawing and writing. Certainly some of the older ones didn’t even want to hold a pen or put a mark on the paper. You’re having to adapt for certain situations, so you’d want to have a bit more time in preparation to allow for this. You can either do it on paper (as we did) or you can draw something with sticks in the ground and add local materials like bits of sari, twigs, stones etc. But that was the whole point of the piloting. So the main barrier I think initially was literacy, and not wanting to or not feeling confident to draw a mark. They were quite happy talking about things. We ended up using post-its so they stuck things rather than mark the paper. We were then able to discuss what and why they were adding to the body – which is a key point of the activity. So that was the first one: body mapping.

“…it is interesting to know how certain common public spaces like the community hall are dominated by the men’s presence.”

KA: Apart from that, it was raining most of the time during the field work, and the participants had limited time available to dedicate to the activities. Considering the muddy surrounding, and rains, use of chart papers, pens and post-its was viewed as an easier tool for participants than gathering and using the local items. Even though the participants were hesitant and shy in the beginning to hold a pen and draw, they began enjoying it while appreciating each other’s efforts. It was observed that the participants could express and understand the key issues of discussions more conveniently through this method.

CM: Next we should have done the social relations technique. For this method you use a pre-drawn diagram of concentric circles and using small dolls/stones place these within the circles indicating the people who are close to you in order of emotional closeness. Questioning around these diagrams can give us an indication of the quality of people’s relationships and type of support they may be able to access. That day when we turned up, most of the group involved in the first session were out in the fields because they’d had pre-monsoon rains making it ideal for planting. So we ended up in a different building which was close to the farm and we had to adapt. While they’re doing their occupations, why not talk about the things that they do in their daily lives and how that impacts them? So we did the occupational mapping technique instead: they talk about their day-to-day activities in their village, and where their activities will take them, whether it’s to a pre-school, the farm, or collecting water or wood, and places of importance and distances travelled.

It was during this second session that we found out that their community building, which I thought was this fantastic resource in the middle of the village, really central, and looked quite comfortable, was not actually considered a space for women. The building also contained a Hanuman temple and only men can go in there. So the building isn’t somewhere women would feel comfortable normally, and when they’re menstruating they can’t go there at all. It’s useful doing these different techniques over a period of time and at different times, because these things just emerge sometimes. Perhaps they wouldn’t have thought about telling us that until they were [doing the occupational mapping]. It’s interesting to think about that when you’re trying to develop techniques that will work for everybody. I think we did the right thing in trying to separate both the genders and age groups, I’m sure that made it easier for discussions to flow.

KA: Also, it is interesting to know how certain common public spaces like the community hall are dominated by the men’s presence. Apart from that, the women mentioned also could not interact with Panchayat Office members comfortably on a regular basis for redressing their grievances regarding various government schemes as the local male Panchayat Officials are mostly drunk. A moderate sized piece of land is also used as a cricket ground exclusively by the young men of the village, however any such space for the recreational activities for women was lacking. As rightly mentioned by Carol, such crucial information from the gender perspective was revealed in discussions related to occupation mapping especially due to the homogenous focus groups of the participants.

GB: Were there any other unexpected challenges?

CM: We did know the monsoon was going to be an issue. Regardless of that, there’s going to be things if you are dependent on agriculture that are always going to be an issue – seasons, weather, and different commitments during different seasons. I don’t think there’s ever a time when people will just be sitting twiddling their thumbs. That was not unexpected, but it makes you aware that people are very dependent on all manner of things. When we first went there didn’t seem to be any men about. It’s the women mainly that seem to be working on the local fields, as well as some older men and older children, the husbands of half the women were away doing other labouring and carpentry jobs. It’s very much dictated by the availability of work.

The pre-monsoon rains made the grounds ideal for rice planting so the villagers said they were unable to take part in further activities for about a week. It’s difficult by the sound of things to work around this issue particularly for women, because if they’re not doing their paid work in the fields, they’re looking after children, gathering wood, doing everything else until they collapse into bed at night. Some of the younger women had been out in the fields since about 8am when we arrived, so our session was almost like their break. And even then they were still going off to get water to wash, to clean, and to drink – and that’s during their break.

KA: A major challenge for the study was to be able to conduct extensive sessions for each of the age and gender groups that we had planned initially. As every group activity included the participant’s active involvement and engagement, being able to have the same participants for all four activities was quite a challenge. Sometimes new participants would be curious and interested to join the group activities whereas at other times, the participants from a previous fixed group may not be able to continue for all the sessions due to personal or work related commitments or urgencies. Therefore, it was a difficult task to conduct all activities according to the convenience of all the participants amidst the rainy season.

GB: How do you ensure in these contexts that a range of voices are heard e.g. of different ages, genders, abilities?

CM: Khushboo and Siva Raju were particularly concerned that men and women were better off being kept apart, because it might restrict how comfortable they felt talking about certain things. And in fact that did happen. In the second session while the women were all doing the activity, a couple of the men that had been in the fields too came into the room we were working in, and straight away you could see the dynamic changed. As I said [the women] were feeling quite insecure about writing, and they were laughing at each other drawing, and at their confidence with the pens and things like this. The minute the men were there [they were saying] “why don’t you do this” and “oh you must put this in”. So I think it was quite good they were able to do and say their own things there.

The plan is that these activities all feed into a social development action plan, where you start bringing all these individual bits and pieces together to discuss the different perspectives. I think it’s important that initially you get perspectives from the individual groups. When we had this massive group of all the different ages you could definitely see that the middle-aged women tend to be a bit more confident. The younger ones tend not to say anything until they were asked, and the older ones seemed to take a step back as well. In their own groups they might feel more confident to talk about their own issues – which may be quite distinct to those of the other age groups.

KA: I think that is where the role of the researcher is important to kind of moderate the discussions. Individuals have different personalities and when they are in groups, they behave differently as well. Some like to lead the discussions while others may just like to nod or agree or keep silent when discussing issues in groups. While explaining the group activities as well as performing them, as a facilitating researcher you have to encourage those who are shy to speak up or simply withholding themselves. On the other hand, those participants who are speaking a lot on others’ behalf or dominating the discussions, need to be moderated. A similar trend was seen among the participants. The middle aged men and women were observed to be much more confident and vocal as compared to the elderly ones who rarely utter a word even though they were the part of the discussions.

“It’s about using the skills and facilities and natural resources and infrastructure, and bringing them all together to make something that’s relevant to people and their circumstances.”

GB: Why is it so important for us to hear a range of voices?

CM: The community building with the temple attached particularly highlights how you might create something wonderful, but it’s got to be something that everybody is comfortable using – unless you are happy excluding particular groups. It’s about listening to what people suggest and understanding where people are coming from and why it’s important. The point of all the different exercises was looking at individual skills and capabilities, and how in small social networks we support and are supported, and on the broader scale what’s important within the village. It’s about using the skills and facilities and natural resources and infrastructure, and bringing them all together to make something that’s relevant to people and their circumstances. It’s making sure that it is something that actually comes from the requirements of the villagers – and it’s probably not going to suit everybody – but hopefully the majority, and we certainly don’t want to make those who are already marginalised more marginalised. And we want to see something that is sustainable as opposed to “you’ve got a bit of money to do this” but it’s not actually going to live beyond the short term.

KA: The communities in rural in general and tribal in particular in India are very heterogeneous in nature. I believe the whole idea of developing strategies for public involvement was to keep the communities in the centre of a model wherein they would build their capacities and make themselves aware and empowered with some support of research and resources available. The larger objective could be maintaining the sustainability of the community resources and bringing development while being able to solve various existent problems related to access to water, healthcare services, education, infrastructure, transport and others, by networking with concerned stakeholders on a regular basis.

This social work carried out by Carol and Khushboo is crucial to ensure that the community’s needs, including those of any underrepresented groups, are at the heart of the buildings we design. It is the first step towards demonstrating how a different kind of building, one that doesn’t cost the Earth, can have a positive impact on the people who inhabit them as well.

See the video below for more on how SUNRISE, SPECIFIC, and the Active Building Centre work together to show how buildings can be designed differently:

Read other blogs in this series with SPECIFIC and the Active Building Centre:

Blog #2: Designing Active Buildings

Blog #3: The Active Classroom: still providing insights and performing well

Blog #4: Translating ‘Active Buildings’ to India: Q&A with Arunavo Mukerjee

Blog #5: Active Buildings for Future Generations

Blog #6: Solar Heat Storage: Eliminating Gas Heating

Blog #7: How renewable energy can transform slum communities: Q&A with Dr Minna Sunikka-Blank