To carry out monitoring and evaluation of the new Solar OASIS building, our community involvement team were awarded some funding from the British Academy/Leverhulme Small Research Grants. As part of this project (DEBATE), we worked with InsightShare and the Tata Institute of Social Sciences to provide Khuded villagers with the means to create their own short films exploring the impact of the building from their perspective. Read on to find out how it went…

“Energy is the golden thread that connects economic growth, increased social equity, and an environment that allows the world to thrive” (then UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon at the Center for Global Development event on “Delivering Sustainable Energy for All; Rio 20 April, 2012).

It was certainly a sharp contrast heading from Swansea on a cold November day to a hot and frenetic Mumbai. There was a similar contrast when heading to Khuded village, the site of the Solar OASIS – India’s first Active Building. Though only about 3 hours away from Mumbai, the lush, quiet green village of Khuded with breathable air seemed a million miles away and indeed very much like an oasis. But the reality for those living there isn’t always as idyllic as it initially seemed to me. For a start it is not always this green. A late monsoon (unpredictability so – and yet another indication of global warming) had ensured that there was still water available in the wells and the crops had benefitted too. The lack of reliable electricity and a phone signal throughout the village are also indications that ‘energy as a right’ expectations are not met here yet. But these were my initial views, and I was here to work with my colleagues from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS-Mumbai) to find out what some of the villagers from Khuded thought about their new solar building.

To provide some background, I am a researcher based at Swansea University and I have been working within SUNRISE since 2019. The Solar OASIS community building was designed and constructed by this international partnership to provide a solution to rural energy access and sustainability. The villagers were encouraged to be involved in the process from the outset, and participatory approaches have ensured that their input fed into the design and functionality of the building. India is one of the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases globally but has made a commitment to increase renewable energy technologies and in particular solar energy. India’s commitment at COP 26 was to get half of its energy from renewables and to reach net zero by 2070. There are several reasons for escalating renewable energy rollout in India, including advancing economic development, improving energy security and mitigating climate change (Kumar. J & Majid, 2020). Decentralized/off-grid technologies, in particular, can offer new opportunities for social empowerment in rural locations.

Often the success of such projects is measured in terms of technical or economic achievements, but this project wanted to understand what success (and impacts) looked like from the perspective of the villagers. Generating, valuing and sharing knowledge from different perspectives are essential to understand what changes or actions may be required during renewable energy transitions. This is particularly important when considering any sociocultural practices (Gaventa & Cornwall, 2006; Yadav et al., 2021).

Research aim

Our research aims were to provide a better contextual understanding of a shift to renewable energy in the new community solar building and how well it was fulfilling needs from the perspective of a diverse group of villagers. The research approach reflects other work that recognises that experience is a basis of knowing and that this legitimate knowledge can influence practices (Baum et al., 2006). Listening to the villagers can also challenge assumptions around the expected benefits of increased access to renewable energy (Sovacool et al., 2023). All ethical approvals were granted by Swansea University prior to the research taking place.

We used a Participatory Video with Most Significant Change (PV-MSC) approach and all researchers involved were trained by InsightShare. This was intended to provide the opportunity and skills for the participants to identify significant changes to their daily life and the tools (such as the phone camera, microphones, tripods etc.) to present them. There has been little similar research that has looked into social and economic priorities within new energy systems and how well community needs may then be integrated into further developments of renewable energy projects (Di Giulio et al., 2016).

Recruitment and PVMSC sessions

A local non-governmental organisation (NGO), Keshavsrushti, has been working within the village for several years and helped us to recruit the final 13 villagers representing different age groups and genders to take part in all the activities. The NGO was also critical in making sure that we progressed through all the necessary channels regarding the local approvals with the Gram Panchayat.

It had been quite a difficult job to find suitable dates and times to carry out the PVMSC activities – partly researchers’ availability but mainly due to the villagers’ commitments to the many activities that had to be worked around to ensure minimal disruption to them. As well as other everyday roles (more details in the film), the long, late monsoon had delayed the harvest where all help each other to complete this task, a pilgrimage followed with many villagers taking part and then Diwali, where celebrations took place over the holiday period and some returned to their home villages.

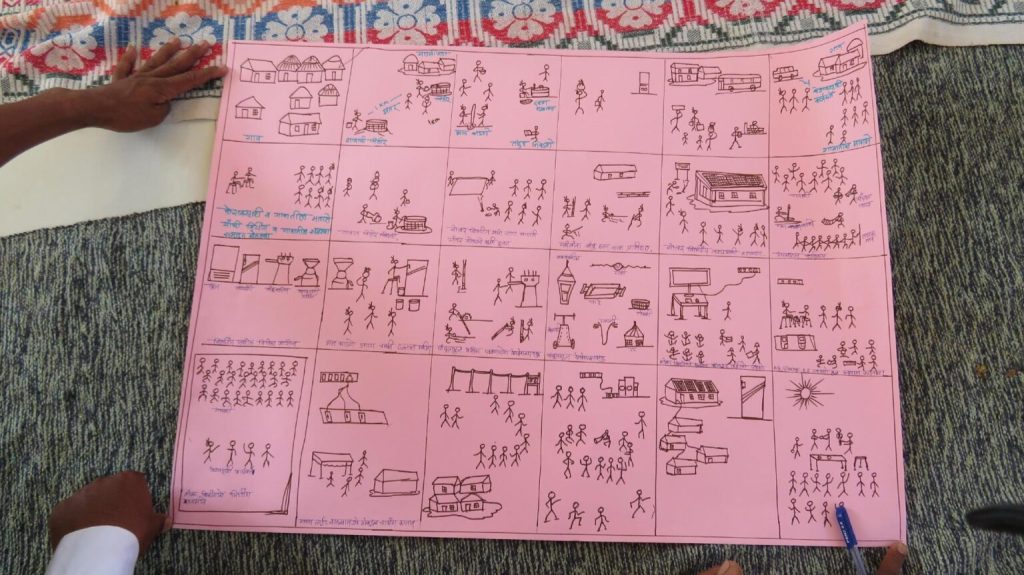

The villagers (8 women and 5 men) took part in PVMSC over 10 sessions in November and early December 2022. The sessions varied between 90 mins and 3 hours with a planned break for refreshments and a chat. It was very important for us to make sure the activities felt like fun and were valuable to the villagers too, considering the time they were committing to this. In fact, we had only intended to have about 5-6 sessions, but the villagers were keen to capture the stories they had talked about while developing their amazing storyboard for the main film (see image below) and also for all to be part of the editing process.

The key question

One key question was posed to those taking part: “What has been the most significant change in your life/livelihood since the solar building has been completed and in use?” The villagers themselves determined the significance of the change to their lives and livelihoods in both smaller and larger groups at first each telling their own story. The telling, re-telling and discussion of narratives of importance alongside the group members posing more questions allowed critical reflection over the sessions. The discussions supported the decisions to include the variety of topics detailed within first the storyboard and ultimately the films created.

The sessions generally took place in the early afternoon after the main daily chores had been completed and prior to evening meal preparation and the family coming together. The sessions covered in brief:

- Information about the research activities, questions and consent

- Introduction to PV-MSC and the phone camera and equipment by filming during games. Initial storytelling in small groups

- More filming games and accruing skills and techniques; developing stories -elaboration and questioning (river of life)

- Initially 2 separate stories (men -focus on computer/education and knowledge transfer) and women- using the equipment); filming narrations

- Why are we telling the stories what are the messages to share with whom – how do we capture the stories? Storyboard discussion and development; capturing ideas from storyboard

- Filming and sharing/demonstrating the importance of Participatory Editing

- Play film to date, editing and additional filming

- Additional filming and editing, additional consent process

- Pre-screen and final editing, consent and completing credits and title of the film

- Final pre-screen and evening Screening to the community

The final film depicts the negotiated and agreed most significant changes to lives and livelihoods following the construction of the Solar OASIS. Participants determined what was important to capture and ‘measure’, for example, in terms of time saved or potential economic opportunities. The discussions and film revealed key themes observed by the participants and discussed with the researchers around differences between ‘before and after/then and now’: changes to daily life and reduced pressure of work; economic opportunities; health and educational opportunities. Encouraged by the researchers to think of what may be next in terms of the solar building’s use, the villagers proposed a number of future improvements and plans.

The film was screened at the solar oasis on the final day of the researcher’s visit. While it was envisaged (by the researchers) as an opportunity to support the realisation of further developments by those outside the village in a position to help, or prompt further discussions within the village, it was mainly seen by participants as a celebration and a chance to share the fortnight’s PVMSC activities with invitees including family members and other villagers (approximately 80 people including children).

And for the future…

The Solar OASIS was still relatively new and had only officially been ‘open’ since the end of October, so was still something of a novelty when we visited. The learning experience for me was huge, and I certainly valued this opportunity to be part of the discussions (via my TISS colleagues’ translations!) and share in the enthusiastic demonstrations of traditional food (rice) preparation and the new equipment, as well as traditional dancing which sadly I did not master! The group reflections of future needs demonstrate desires for further development (including income-generating schemes) and opportunities to ensure that benefits reach all households. Watch this space for further updates.

Thanks to

I would firstly like to thank all the participants in this research who so generously gave their time and energy to the activities. Tata Institute of Social Sciences colleagues Khushboo Ahire and Dr Gandharva Pednekar led the activities in Khuded, and Professor Siva Raju (TISS) and Professor Minna Sunikka-Blank from Cambridge University were Co-Investigators in the study, Dani Kalarikalayil Raju was invaluable in his technical support when we were carrying out participatory editing and at the Khuded premiere. Also, there was a supportive cast in the form of colleagues from InsightShare (Soledad Muniz and Tricia Jenkins) who not only provided our PVMSC training but were ready and available with advice via WhatsApp while we were in the field.

Learnings from the research experience

The participatory video with most significant change (PVMSC) monitoring/evaluation and post-build survey phases were initiated earlier in the project timeline than planned due to delays in the Solar OASIS construction and full operation as a result of the pandemic and the approach of project deadline and funding. The videos have been created by the community members, and the coverage in the videos represents a snapshot of some community members’ experiences. Full project findings will be reported in the coming months. Since the project is just completing its first year, its sustainability will need to be studied further.

We will be presenting sections of the community film and additional research findings at the Visual Methods Conference in Rome in May and also at the BA summer showcase in London in June.

Bibiliography

Baum, F., MacDougall, C., & Smith, D. (2006). Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(10), 854–857. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.028662

Di Giulio, G., Groves, C., Monteiro, M., & Taddei, R. (2016). Communicating through vulnerability: Knowledge politics, inclusion and responsiveness in responsible research and innovation. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 3(2), 92–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2016.1166036

Gaventa, J., & Cornwall, A. (2006). Challenging the Boundaries of the Possible: Participation, Knowledge and Power. IDS Bulletin, 37(6), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2006.tb00329.x

Kumar. J, C. R., & Majid, M. A. (2020). Renewable energy for sustainable development in India: Current status, future prospects, challenges, employment, and investment opportunities. Energy, Sustainability and Society, 10(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13705-019-0232-1

Sovacool, B. K., Bell, S. E., Daggett, C., Labuski, C., Lennon, M., Naylor, L., Klinger, J., Leonard, K., & Firestone, J. (2023). Pluralizing energy justice: Incorporating feminist, anti-racist, Indigenous, and postcolonial perspectives. Energy Research & Social Science, 97, 102996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.102996

Yadav, P., Davies, P. J., & Asumadu-Sarkodie, S. (2021). Fuel choice and tradition: Why fuel stacking and the energy ladder are out of step? Solar Energy, 214, 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2020.11.077

The research was funded by the British Academy/Leverhulme small grants “Determining Equitable Benefits: Achieving Transitions in renewable Energy (DEBATE)”.